Tectonic plates are always moving under your feet. This constant lithospheric motion results in surface fractures in the Earth’s crust, which are called faults. Large faults also appear in the boundaries between tectonic plates. Keep reading to learn more about the three main types of faults – normal, reverse, and strike-slip faults – as well as places in the world where you can find them.

Parts of a Fault

Faults consist of two rock blocks that displace each other during an earthquake or regular tectonic movement. One block is called the hanging wall, and the other is the footwall. Understanding the parts of a fault can help you identify what type of fault you’re seeing.

The main parts of a fault are:

- Fault plane - the surface area between two rock blocks created by an earthquake

- Fault trace - the visible crack in the Earth’s crust that indicates where a fault is

- Fault scarp - the vertical step that rises during tectonic activity

- Hanging wall - the rock block that hangs over the fault plane

Footwall - the rock block that occurs below the fault plane

The behavior of each of these parts helps earth scientists identify faults as normal, reverse, or strike-slip. Once you know what type a fault is, you can predict what can happen there during an earthquake.

Normal Faults

Normal faults, or extensional faults, are a type of dip-slip fault. They occur when the hanging wall drops down and the footwall drops down. Normal faults are the result of extension when tectonic plates move away from each other.

What a Normal Fault Looks Like

Normal faults create space. These faults may look like large trenches or small cracks in the Earth’s surface. The fault scarp may be visible in these faults as the hanging wall slips below the footwall.

If you’re looking at a mountain that lies on a normal fault, you’ll see that the hanging wall has “dipped and slipped” under the footwall level. This gives the mountain a leaning, sloping look. In a flat area, a normal fault looks like a step or offset rock (the fault scarp).

Normal Faults Around the World

You may see additional examples of normal faults in these places:

- Atalanti Fault (Greece) - fault segment between the Apulia and Eurasia plates

- Corinth Rift (Greece) - marine trench between the Aegean Sea Plate and Eurasian Plate

- Humboldt Fault Zone (North America) - part of the Midwestern Rift System between Nebraska and Kansas

- Moab Fault (North America) - canyon and valley zone on the North American Plate in Utah

- Sierra Nevada Fault (North America) - fault along the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

- Wabash Valley Seismic Zone (North America) - series of faults on the North American plate between Illinois and Indiana.

Reverse Faults

Although reverse faults are also dip-slip faults, they behave the opposite way that a normal fault does. The hanging wall slides up over the footwall during tectonic movement in these faults. Reverse faults with a 45 degree dip (or less) are known as thrust faults, while faults with over 45-degree dips are overthrust faults.

What a Reverse Fault Looks Like

Reverse faults look like two rocks or mountains have been shoved together. Unlike normal faults, reverse faults do not create space. They are found in areas of geological compression.

Reverse Faults Around the World

There are examples of reverse faults in several continents around the world. They are most common at the base of large mountain ranges. Some famous reverse faults include:

- Glarus thrust (Switzerland) - thrust fault in the Swiss Alps

- Longmenshan Fault (China) - thrust fault at the Longmen mountains, between the Eurasian and Indian-Australian plates

- Lusatian Fault (Germany) - overthrust fault between the Elbe valley and Giant Mountains

- San Ramón Fault (Chile) - part of the west Andean thrust fault system at the base of the Andes mountains

- Sierra Madre Fault Zone (North America) - compression fault between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates

- Tacoma Fault (Washington) - part of the Seattle Uplift system between the Juan de Fuca and North American plates

Strike-Slip Faults

Unlike dip-slip faults which move vertically, rock blocks in strike-slip faults move laterally alongside each other. A fault that moves to the left is a sinistral transcurrent fault, and a fault that moves to the right is a dextral transcurrent fault. Strike-slip faults include transform (which end at another plate boundary) and transcurrent (which end before reaching another plate boundary) fault lines.

What Strike-Slip Faults Look Like

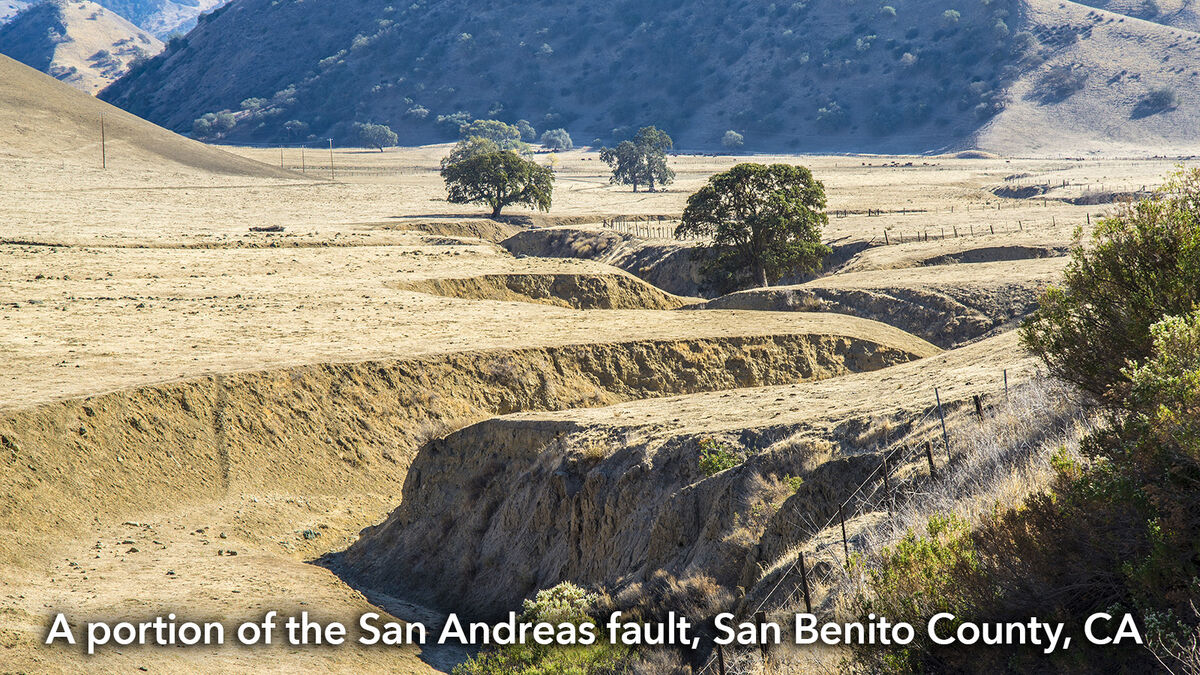

So how can you tell if you’re looking at a strike-slip fault? Many strike-slip faults are found on the ocean floor. But if you’re looking at a strike-slip fault, it may look like the land on either side has moved in opposite directions. This movement may cause offset rivers, parallel valleys, and abrupt ends to mountain chains.

Strike-Slip Faults Around the World

The most famous example of a strike-slip fault is the San Andreas Fault. The 1300-kilometer San Andreas Fault stretches across most of California and divides the Pacific and North American tectonic plates. It is responsible for a number of smaller fault systems across the western United States.

Other examples of transcurrent faults include:

- Anatolian Fault (Turkey) - fault between the Eurasian and the Anatolian plates

- Alpine Fault (New Zealand) - fault between the Pacific and Indo-Australian plates

- Hayward Fault Zone (North America) - transform boundary between the Pacific and North American plates; runs parallel to the San Andreas Fault

- Kunlun fault (Tibet) - fault near the edge of the Eurasian plate

- Yammouneh Fault (Lebanon) - part of the Dead Sea Transform fault system between the Arabian and African plates

Faults Create Earth’s Landforms

Faults mark the edges of tectonic plates and points of lithospheric stress. But they also create the beautiful mountain ranges and valleys on our planet. If you’d like to learn more about landforms and earth science, check out an article that lists examples of landforms around the world.